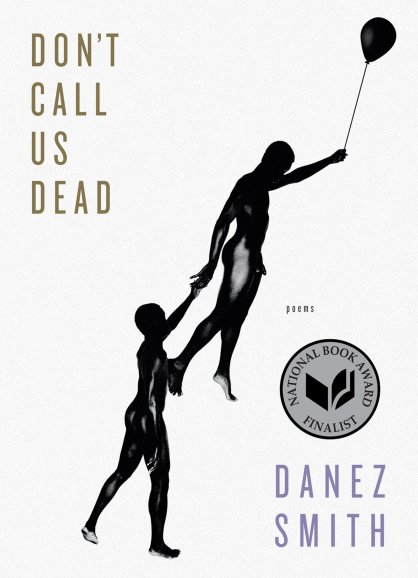

On Thursday, July 23, people from the Lehigh Valley and Philadelphia came together over Zoom to share their insights and reactions to Danez Smith’s powerful and haunting poetry collection, Don’t Call Us Dead. The Queer Poetry Reading Group discussion was hosted by the Bradbury-Sullivan LGBT Community Center, and sponsored in part by the Lehigh Valley Engaged Humanities Consortium and South Side Initiative. A finalist for the National Book Award, Don’t Call Us Dead interrogates the experience of being queer, Black, and HIV-positive in the United States. The reading group unpacked Smith’s dreams of a world where Black people are able to thrive even as it explores the painful realities of anti-Black violence and police brutality. The group also wrestled with the complexities of desire and danger when living with HIV that Smith explores in their poetry.

Smith’s collection begins by imagining an afterlife for Black men shot by the police. They* depict a beautiful space where belonging, safety, and love is found by those who perished from police violence. In one poem, Smith imagines those lost to violence calling out to readers and telling us, “please, don’t call us dead, call us alive someplace better.” Smith creates a new space where the freedom from violence is “someplace better.” They reject the flattening label of “dead,” a label that assumes there is no agency or redemption for Black people murdered by police brutality. Instead, they choose to see them as fully “alive” in a different place, a place completely run by the desires and ideas of Black people.

They also challenge forms of memorializing that flatten and erase the humanity of Black people who have died. They write, “they buried you all business, no ceremony. / cameras, t-shirts, essays, protests / then you were just dead.” Here, Smith highlights how quickly Black deaths can become focal points for competing agendas through “essays” and “protests.” They critique the media’s inability to mourn the loss of a life as news stories become “all business” without “ceremony” that addresses the humanity of the deceased. They use a clinical tone in the poem to demonstrate how Black death is just another storyline to cover. Their collection ultimately challenges us to move beyond an obsession with Black death to see the richness, fullness, and complexity of Black life.

The urgency of our group’s discussion was underscored as members realized that the conversation happened almost two months exactly after the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Smith’s poetry underscores the power and necessity of the Black Lives Matter movement, which, in response to the murders of Floyd, Breonna Taylor in Louisville, Ahmaud Arbery in Glynn County, Tony McDade in Tallahassee, and so many others, inspired global protests. Smith’s poetry allowed participants to discuss recent coordinated rallies organized by Black Livers Matter activists as they call for an end to police brutality and white supremacy. Participants also explored their complicity in white supremacy, their lack of understanding of living as an HIV-positive person, and their participation in justice efforts that flatten or erase Black queer voices and experiences.

For example, some members discussed the recent trend of turning the mantra, “Arrest the cops who killed Breonna Taylor” into a series of memes. The conversation highlighted how social media movements, even when well-intended, end up replicating the very dynamics of erasure and harm Smith wants to avoid. For example, in using the genre of the meme to discuss the complexity of Breonna Taylor’s murder, audiences can unintentionally flatten the intersections of power that led to her death. Memes rarely invite a mournful tone or a complex political analysis because their purpose is to provide pithy and often humorous commentaries. It became clear to each of us that while social media and broader media movements can be powerful tools of advocacy, they alone will never be enough to realize a truly anti-racist transformation.

Other participants struggled with Smith’s depictions of desire and pleasure as they recount the sexual encounters that led to their contraction of HIV. This discussion emphasized the thin line between desire and danger that exists for many in queer (and especially gay) communities. Smith’s poems show how opening oneself up to multiple sexual partners increases both the feelings of pleasure and the dangers of contracting an STI. As an HIV+ poet, Smith focuses upon how their status impacts their sexual life. Narrators in the poems long to enjoy freedom in their sexual encounters, but find themselves worrying about transmitting the virus or partner’s judgement and rejection because of their status. Smith’s own tension between desire and despair helped us sit in the multiple truths of an HIV diagnosis, which enabled us to build a more complex empathy for people living with HIV.

Participants also revelled in Smith’s use of pop culture references. For example, they reflect on their childhood perceptions of race and film through Jurassic Park and dinosaurs in the poem “dinosaurs in the hood.” We also explored the import of popular culture in Smith’s poem “blood hangover,” which is a play off of Diana Ross’s 1976 song “Love Hangover.” In this poem, Smith uses Ross’s lyrics to convey the yearning for a cure for HIV. They write, “i’ve got the sweetest hangover / i don’t want / yeah i want to get / over / ooh no cure / i need cure.” We considered how Smith’s play with pop culture enables us to enter these difficult conversations more openly. We also highlighted how integral it is for us to pay attention to the artistic and intellectual contributions of Black artists and thinkers in a world that wants to focus on Black destruction. Ultimately, this conversation was possible because of the incredible artistic work of a queer, Black, nonbinary, HIV-positive poet.

The conversation left the group wanting to revisit Smith’s work with these new insights in mind. We were deeply aware of how much our discussion barely scratched the surface of the collection’s richness, and, yet, it excited us to go back and reread Smith’s work with new questions. We named how important it is to look at justice issues such as anti-racism and queer liberation within a framework that recognizes how LGBTQ people are impacted by multiple identities at the same time. Members also named how they wanted to commit themselves to learning more not only about HIV and healthcare, but also LGBTQIA+ healthcare in America more broadly.

Ultimately, Smith’s poetry encouraged members to resist easy and monolithic narratives about marginalized communities in favor of more complex and intersectional approaches that require tension and nuance. Smith’s work highlights the necessity of queer Black voices to depict a fuller humanity that exists at the intersection of multiple truths. In this way, Smith’s collection affirms the reason this poetry group began in the first place: to provide a space for LGBTQIA+ people and allies from different walks of life to come together, to build community and resiliency, and to discover the transformative potential that poetry can offer.

*Danez Smith uses “they/them/their” pronouns.